2023 Update: Will $2 Trillion in Climate, Water, and Infrastructure Investments Go Where It’s Needed Most?

A 50-State Survey of State Policies to Help Ensure Federal Investments Benefit “Disadvantaged Communities” Under Biden’s Justice40 Initiative

Executive Summary

With historic federal funds coming from the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL), the Creating Healthy Incentives to Produce Semiconductors and Science Act (the CHIPS Act), remaining American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) funds and more, the federal government has authorized over $2 trillion in investments in climate, infrastructure, clean energy, and water to be released over the next 5-10 years. Biden’s Justice40 Initiative (Justice40) requires that at least 40% of the benefits from these federal investments go to disadvantaged communities (DACs) that are marginalized, underserved, and overburdened by pollution, a term that is defined differently at federal and state levels and even between different federal programs. Biden’s Justice40 Initiative also requires meaningful community engagement between state and local decision-makers and communities in making federal funding decisions. It will take careful coordination between communities and all levels of government to meet Justice40 targets to make sure this historic level of funding goes where it’s needed most.

In 2022, L4GG created a 50-state dashboard of the existing state-level policies, maps, and decision-makers identifying DACs to facilitate Justice40 implementation and to assist communities and advocates in identifying state decision-makers holding the purse strings.

This 2023 version of the dashboard includes: an updated overview of the various definitions and data available for identifying DACs and environmental justice communities; all known, existing, or proposed state-level policies for Justice40 implementation; and the names and contact information for relevant state-level decision makers and agencies regulating climate, energy, water, and infrastructure to facilitate community engagement.

In addition, the 2023 update also includes the following new information:

Detailed comparison of state-level DAC maps to the federal Climate and Economic Justice Screening Tool (CEJST Map), revised in December 2022;

A brief discussion of the impact of using race as a metric in the wake of the affirmative action decision, Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard; and

Example state-level policies and best practices related to:

Community Engagement;

DAC Definitions and Mapping; and

Justice40 Implementation.

The information provided herein can be used in a variety of ways. State decision-makers can use this report to identify DACs within their jurisdiction, prioritize federal funding for vulnerable communities, enhance community engagement, and identify example policies from other states for implementing Justice40. Local governments and communities can use this report to determine whether they are (or should be) identified as a DAC for priority funding and to facilitate more meaningful community engagement. Nonprofits and advocates can use this report to identify and determine the best entry points for advocacy. Finally, federal agencies can use the state-level mapping data to enhance existing federal maps and to identify data gaps.

Meeting and exceeding Justice40 is a critical first step to addressing historic inequities in this country and the equitable implementation of BIL, IRA, and other federal programs. A federal investment of this magnitude has the potential to either start to tackle historic inequities and global warming or exacerbate environmental racism and the climate crisis if it is not allocated where it is needed most: to the communities of color and low-income communities that have been left behind for decades and are most vulnerable to the impacts of climate change. As this report shows, the country still has a long way to go to meet the Justice40 directive.

UPDATES TO Existing Federal Guidance on Disadvantaged Communities and JUSTICE40

In January 2021, the Biden Administration launched the Justice40 Initiative by Executive Order 14008 to address long-standing climate and environmental inequities. Justice40 requires federal agencies to work with states and local communities to ensure that at least 40% of the benefits from federal climate, clean energy, water, and infrastructure investments go to DACs that are marginalized, underserved, and overburdened by pollution. Justice40 is a critical piece of the Biden Administration’s larger initiative to achieve at least a 50% reduction in (2005) emissions by 2023. Justice40 is designed to ensure that historic federal investments from BIL, IRA, remaining ARPA funds, the CHIPS Act, and other federal laws directed towards climate, clean energy and energy efficiency, clean transit, affordable and sustainable housing, training and workforce development, and clean water infrastructure benefit overburdened communities to level the playing field and to address past environmental harms. The Biden Administration’s Office of Management and Budget (OMB) issued interim guidance on July 20, 2021 regarding Justice40 implementation and additional guidance in July and August 2022, identifying the hundreds of programs covered by Justice40. In addition to EO 14008, the Biden Administration issued EO 13985 (requiring federal agencies to conduct an equity assessment that includes examining potential barriers faced by underserved communities), EO 14091 (creating agency equity teams, a White House Steering Committee on Equity, and requiring federal agencies to establish equity action plans), and EO 14096 (further pushing Biden’s whole-of-government approach to environmental justice) to further address existing environmental inequities.

Defining DACs and Mapping at the Federal Level

Under the interim OMB federal guidance, a “community” is defined as: “either a group of individuals living in geographic proximity to one another, or a geographically dispersed set of individuals (such as migrant workers or Native Americans), where either type of group experiences common conditions.” The 2021 guidance directed federal agencies to determine whether a specific community is disadvantaged based on a combination of variables that may include, but are not limited to low income, low poverty rates, high unemployment, linguistic isolation, impacts from climate change, access to water, and other criteria.

To facilitate the implementation of Justice40, the White House Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ) published the Climate and Economic Justice Screening Tool (CEJST Map), most recently updated in November 2022, which identifies the location of DACs nationwide based on a number of factors, consistent with the OMB guidance. The CEJST Map is organized according to census tracts and identifies a community as disadvantaged if it is in a census tract that is: (1) at or above the threshold for one or more environmental, climate, or other burdens, and (2) at or above the threshold for an associated socioeconomic burden. In addition, a census tract that is completely surrounded by disadvantaged communities and is at or above the 50% percentile for low-income is also considered disadvantaged in the CEJST Map.

A noteworthy critique of CEJST is that the map lacks identification of cumulative burdens. In CEJST, a neighborhood either meets a threshold burden, or it does not. There is no measure that looks at the cumulative number of threshold burdens. Accordingly, one neighborhood could meet the threshold for three criteria, and another neighborhood could meet the threshold for one criteria, yet the cumulative impact of meeting the threshold burdens across multiple criteria would not be identified.

In addition, the CEJST Map does not include race as a factor. Instead, the CEJST Map indirectly prioritizes BIPOC communities through the use of a new indicator, the “historic underinvestment” indicator, which comprises data from census tracts that experienced historic underinvestment based on redlining maps created by the federal government’s Home Owners’ Loan Corporation between 1935 and 1940. A recent WRI Report found that including the historic investment indicator data in the revised 2022 version (CEJST 1.0) identified higher shares of minority populations than the original CEJST Beta version; however, the overall percentage of minority populations identified in CEJST 1.0 actually went down.

In addition to CEJST, several federal agencies have developed mapping tools specific to their jurisdictional areas for purposes of implementing Justice40. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has maps such as the Environmental Justice Screening and Mapping Tool and launched the EPA Office of Environmental Justice and Civil Rights to help implement Justice40. The U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) and the U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT) also have agency-specific maps to support Justice40 implementation of their respective federal programs, including DOE’s Energy Justice Dashboard: Disadvantaged Communities Reporter and DOT’s Transportation Disadvantaged Census Tracts Map, the Equitable Transportation Explorer, and the EV Charging Justice40 Map. A list of several federal DAC mapping tools is available here. In addition to covering slightly different data, it remains somewhat unclear exactly how each map must be used and applied under each federal program.

It is also critical to note that any map is only as good as the data underlying said map. It will be important for federal agencies to encourage and incorporate receiving new and updated localized data to continually update and improve mapping data.

DAC definitions in Water AND Infrastructure

Long before Justice40 was established, and the term “disadvantaged community” became a critical legal definition, states were required to consider affordability and other criteria for identifying underserved communities in the water context. Both the Clean Water Act (CWA) and the Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA) include provisions to prioritize water infrastructure funding for communities in need. These frameworks, called state revolving funds (SRFs), are federal-state partnerships that provide low-cost financing and principal forgiveness to communities for certain clean water and safe drinking water-related projects. SRFs are governed by federal law, but provide states with flexibility for selecting and financing water-related projects in order to meet local needs.

Specifically, Section 603(i) of the CWA, amended in 1987, details how a state Clean Water State Revolving Fund (CWSRF) program may provide additional subsidies for communities in need and requires each state to establish affordability criteria for the program.¹ The SDWA was amended in 1996 to establish the Drinking Water State Revolving Fund (DWSRF) program to assist with financing the costs of infrastructure upgrades to water systems to address public health needs. Section 1452(b) of the SDWA requires that each state prepare an annual Intended Use Plan (IUP) to identify the proposed use of funds in the drinking water context.² Section 1452(d)(3) defines the term “disadvantaged community” in the drinking water context to mean the service area of a public water system that meets affordability criteria established by each state.³

BIL amended the CWA and SDWA to provide an even greater subsidy for DACs through loan principal forgiveness, grants, and negative interest loans.⁴ In addition, the EPA issued guidance requiring states to define a disadvantaged community in order to be eligible for federal subsidies under the SRF program. In response, states have been adding more specific DAC definition criteria and revising existing affordability criteria in the SRF context. States often implement these changes by providing more detailed DAC definitions in the appendix to the State’s IUP, which are revised on an annual basis.

While several states have yet to directly address equity in climate or energy, they have established DAC definitions and affordability criteria in the water context to secure additional funding. For this reason, the State-Level Findings include analyses for each states’ definition of affordability criteria and, if applicable, disadvantaged community criteria (or similar term) in the states’ clean water and drinking water context.

Each state manages its SRF differently, using a unique set of laws and regulations available in state regulations, IUPs, and other guidance documents. While the State-Level Findings in this report provide a high-level overview of how each state defines its affordability criteria in the water context, practitioners should consult a states’ most recent IUP and applicable laws, regulations, and guidance documents in order to have a complete understanding of the states’ principal forgiveness financing framework (including applicable thresholds, how criteria is weighed, and the relevant formula) to determine financing eligibility for disadvantaged and overburdened communities under the SRF program.

Questions Covered IN STATE-LEVEL FINDINGS

To facilitate Justice40 implementation, the State-Level Findings describe existing state-level DAC or similar definitions in the climate, equity, and water context found in state law, regulation, guidance, or policy, along with any relevant DAC mapping tools in active use or development, and a comparative analysis of the criteria used in the DAC mapping tools against CEJST 1.0 (updated November 2022) for each state, including Washington D.C. and Puerto Rico. In addition, the State-Level Findings identify the state-level decision makers, agencies, and offices regulating equity, climate, infrastructure, energy, and water in each state to facilitate meaningful community engagement and assist coalition partners with advocacy efforts. Note that the State-Level Findings do not identify State Energy Office contacts because that information is already available by NASEO. Finally, the State-Level Findings identify whether the state has enacted or is considering laws, policy, or guidance related to the implementation of Justice40 to provide model policies to consider and to highlight the existing gaps in policy.

For additional details regarding our approach to the legal research and methods, click here.

Example Policies and Best Practices to Consider⁵

As state governments across the country continue to develop definitions for DACs, embrace community engagement principles, and implement Justice40, they are developing policies and legislation that can be used by other states as potential model policies to explore and consider. Below we have highlighted a few laws and policies found in states across the political spectrum, including states with Democratic supermajorities, Republican supermajorities, and bipartisan leadership that fall within the following three categories: (1) legal definitions for DACs; (2) implementing Justice40; and (3) embracing community engagement principles. Note that this section does not highlight laws or policies that were proposed but failed to pass; however it does highlight at least one policy that is still pending before the legislature. Critically, the success of each law or policy varies widely depending upon its enforcement and implementation; without sufficient tracking, implementation, and enforcement, a policy that looks good on paper may be deemed completely ineffective in practice.

Defining DACs: Example Policies in Blue, Red, and Purple States⁶

While the State-Level Findings provide a detailed analysis of the status of each states’ definition, a few State DAC definitions are worth highlighting.

DAC Definitions: Blue States

New York’s Senate Bill 6599, the Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act (CLCPA), passed in July 2019 and is arguably the most equity-centric law of the country, often referred to as the precursor to Biden’s Justice40 Initiative. A key element to the CLCPA includes establishing a Climate Justice Working Group (CJWG), comprising members of environmental justice communities, and various state agency representatives. The CJWG is tasked with identifying criteria for identifying and defining DACs for the purposes of co-pollutant reductions, greenhouse gas emissions reductions, regulatory impact statements, and the allocation of investments related to CLCPA. In March 2023, the CJWG voted to approve and adopt the final DAC criteria, which includes two types of data): (1) environmental burdens and climate change risks and (2) population characteristics and health vulnerabilities.⁷

Minnesota’s HF 7, signed into law on May 24, 2023, defines an “environmental justice area” to be one or more census tracts in which: (i) 40% or more of the population is nonwhite; (ii) 35% or more of the households have an income at or below 200% of the federal poverty level; (iii) 40% or more of the population over the age of five has limited English proficiency; or (iv) is located within Indian Country. HF 2310, referenced below under the community engagement section, contains the same new definition.

The Minnesota law offers a simpler definition when compared to the New York law, but it too identifies communities in need based on certain demographics. Both the New York and Minnesota laws include race as a factor (see below for a discussion on including race in definitions).Colorado H.B. 21-1266, the Environmental Justice Act, was signed into law in July 2021. It defines “disproportionately impacted community” as a census block group in which: (1) more than 40% of the households are low income or identify as minority; (2) the proportion of households that are housing cost-burdened is greater than 40%; and (3) any other community identified or approved by a state agency as “disproportionately impacted” if the community has a history of environmental racism perpetuated through redlining, anti-indigenous, anti-immigrant, anti-hispanic, or anti-black laws; or (4) the community is one where multiple factors, including socioeconomic stressors, disproportionate environmental burdens, vulnerability to environmental degradation, and lack of public participation act cumulatively to affect health and the environment and contribute to persistent disparities….”

This definition is particularly noteworthy because it includes historical disparities such as redlining. Note that this policy also uses race as a factor.California does not use race as a factor and takes a more nuanced approach, granting state agencies (CAL EPA and California Air Resources Board) the authority to designate disadvantaged communities for purposes of identifying necessary clean energy investments based on a multitude of factors. See CalEnviroScreen DAC Map.

DAC Definitions: Purple States

Vermont, a state led by a Republican Governor with a Democrat-led state legislature, created a definition for “environmental justice populations.” Vermont S. 148, signed into law on May 31, 2022, defines “environmental justice population” to mean “any census block group in which: (A) the annual median household income is not more than 80% of the State median household income; (B) Persons of Color and Indigenous Peoples comprise at least six percent or more of the population; or (C) at least one percent or more of households have limited English proficiency.”

DAC Definitions: Red States

L4GG could not identify a conservative state with a clear DAC definition passed by the legislature. However, all states are required to to submit an annual Electric Vehicle Infrastructure Deployment Plan (NEVI Plan) to the DOT and the DOE, describing how the state intends to distribute funds under the National Electric Vehicle Infrastructure Formula Program consistent with Justice40 If done correctly, these plans can provide useful guidance in more conservative states on how to identify DACs for purposes of Justice40.

For states that do not otherwise have helpful DAC mapping or local information, state agencies and local governments within that state can use the Federal Mapping Tools available to identify DACs for Justice40 compliance. In addition, conservative states may have existing and helpful DAC definitions established in the SRF water context. For example, North Dakota does not have a disadvantaged community (DAC) definition concerning energy, equity, or climate, but offers an interesting DAC definition in the Intended Use Plan created under the state's water programs, which uses income, employment levels, education, and percentage of income used for water services to determine if an area is disadvantaged.

Additional Considerations in DAC Mapping: One important consideration and function to include in any DAC mapping policy is to allow communities to submit information to self-designate. The flexibility to self-designate as a DAC ensures that communities have a say in how their community is being defined by state decision-makers and ensures that local demographic data can be updated and incorporated, as necessary, to reflect more accurate definition and map, which is critical to the equitable distribution of resources.

Community Engagement: Model Policies in Blue and Purple States

Several states have established policies to ensure meaningful community engagement in state-level decision making and the allocation of federal resources. Again, the effectiveness of these policies will depend in large part on effective implementation.

Community Engagement: Blue States

Two states with Democratic supermajorities—Minnesota and Washington—passed model policies that require community engagement in different ways; Minnesota’s policy employs a trigger built into the compliance and enforcement process, and Washington’s law takes a top-down approach by requiring agencies to implement community engagement into the environmental justice sections of their required strategic plans.

Minnesota’s HB 2310, passed in May 2023, requires community engagement to remedy an environmental harm when there has been a proven violation of a Minnesota Pollution Control Agency (MPCA)-issued permit. MPCA is the state agency charged with regulating pollution, and does so using permits. If an entity violates its permit, it may be subject to paying civil fines to MPCA. Under HB 2310, when the MPCA recovers over $250,000 in fines for a permit violation, 40% of the recovered fines are required to be sent to the community health board where the facility that violated the permit is located. The community health board must then meet directly with the residents potentially affected by the pollution, and develop a project that benefits the residents and addresses the residents’ concerns. After receiving the funds, community health boards are required to submit a report to the MPCA one year later that describes the community engagement process employed, the purpose and activities for which the funds were used, and an account of expenditures. Another important aspect of HB 2310 is that it also requires the MPCA to complete a cumulative impact analysis of environmental justice areas whenever issuing a permit.

Washington’s Healthy Environment for All (HEAL) Act addresses community engagement from a different angle: instead of using a statutory trigger that is embedded in the litigation and settlement process, the HEAL Act requires the development of community engagement into State agencies’ strategic plans. The HEAL Act requires the Washington Departments of Ecology, Health, Natural Resources, Commerce, Agriculture, Transportation, the Puget Sound Partnership, and others to incorporate environmental justice implementation into each agencies’ strategic plans. Part of this environmental justice implementation must include “methods to embed equitable community engagement with, and equitable participation from, members of the public, into agency practices for soliciting and receiving public comment.” The HEAL Act came as the result of extensive efforts by coalition partners who remain critical to ensuring the fair and equitable implementation of the policy.

Community Engagement: Purple States

In the category of states that are not supermajorities, and are instead a mix of Democrat and Republican leadership, Louisiana and Vermont stand out for having example policies that prioritize community engagement. Louisiana’s community engagement requirement is in the context of BIL implementation and Vermont’s community engagement requirement is in the context of engaging with environmental justice focus populations more broadly.

Louisiana Governor John Bel Edwards issued Executive Order 22-19 in November 2022. The EO requires state agencies to develop BIL action plans. These action plans require each state agency to define how the agency plans to engage with “local and tribal governments, nonprofits, and other community organizations to increase access to [BIL] funding opportunities.”

Vermont’s S. 148 requires state agencies to develop community engagement plans prior to July 1, 2025. The plans should “describe[] how the agency will engage with environmental justice focus populations as it evaluates new and existing activities and programs.”

For both policies, it will be important to track state agency plans as they develop in order to determine their effectiveness and whether meaningful community engagement has been incorporated.

Community Engagement: Red States

L4GG was unable to identify a state-level policy to ensure meaningful community engagement in a wholly conservative state, but certain states do refer to community engagement in the state-required NEVI process, which mandated a certain level of engagement. One stand-out state includes Tennessee, which published a Tennessee Electric Vehicle Infrastructure (TEVI) Plan that describes how the Tennessee Department of Transportation (TN DOT) should use the federal DAC definition to ensure meaningful community engagement. The TEVI Program Project Team used the DOT’s EV Charging Justice40 Map and conducted targeted outreach regarding the TEVI Program to DACs identified in the map. When tracking and measuring benefits to investments under the TEVI Plan, the TN DOT also used the Appalachian Regional Commission’s assessment of risk counties in identifying DACs.

Additional Considerations for Community Engagement: In addition, cities within more conservative states can take action at the local level to ensure meaningful community engagement in the absence of state-level policies. For example, the City of Cincinnati, Ohio City Council passed a motion in 2015 to “provide broad, inclusive, deliberate, and meaningful participation in the policy process with the general public and stakeholders from the public, private, and nonprofit sectors.” The motion sets forth community engagement principles, such as transparency and trust, inclusion and demographic diversity, and other principles. Local governments can also consider using federal funding to hire community liaison roles to foster more meaningful community engagement.

Justice40: Example Policies in Blue, Red, and Purple States

States with leadership across the political spectrum—Democratic supermajorities, Republican supermajorities, and mixed leadership states—have been taking a variety of steps to implement the Justice40 Initiative and the equitable distribution of federal funding, including creating oversight committees to help ensure implementation of Justice40. That said, Justice40 is meant to apply equally across the country, and currently, only 22 states have existing or proposed laws or guidance to help ensure its implementation.⁸

This map focuses solely on states that have existing or proposed laws or guidance that would help implement Justice40.

J40: Blue States

Illinois established a Justice40 oversight committee in July 2023 to make findings and recommendations regarding the use of federal funds provided to the State to address environmental justice. Delaware established a Justice40 oversight committee in 2021 with a similar function to Illinois, but it is unclear whether the committee has met since 2022. The key to success with these policies is in the execution and whether the committees have sufficient authority to implement Justice40 recommendations.

In addition to oversight committees, states can take action to implement Justice40 by allocating specific resources to DACs. Washington’s HEAL Act establishes a goal of having 40% of grants and expenditures (not just benefits) go to DACs. New York’s S. 6599 requires 35% of expenditures to DACs, with 40% of expenditures as the goal. While California has not been able to pass a comprehensive Justice40 bill even though there’s a strong coalition to pass one including a number of environmental justice organizations, it has established the California Climate Investments Program, which requires that a certain percentage of funds from the proceeds of the State’s Cap-and-Trade Program must be targeted for investment in disadvantaged communities. And finally, the Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy (EGLE) issued Michigan’s Healthy Climate Plan in 2022, which identifies the State’s commitment to ensuring that at least 40% of state funding for climate-related and water infrastructure initiatives benefit Michigan's disadvantaged communities. The Michigan Plan states that EGLE is currently awaiting federal guidance on how to implement Justice40, and in the meantime, is seeking input from environmental justice communities, tribal governments, and other stakeholders.

J40: Purple States

In Louisiana, the Governor issued EO 22-19 “to ensure that [BIL] programs benefit all the citizens of Louisiana and comply with the federal Justice40 mandate, where applicable.”

Similarly, the North Carolina Governor issued Executive Order No. 246 in January 2022, stating that cabinet agencies shall distribute state and federal funds by prioritizing “actions that…invest in historically underserved communities, [and] increase affordability for low- and moderate-income households….”

The reach and effectiveness of the two approaches above have yet to be determined, but if these orders are coupled with specific directives by the Governor that force state agencies to take measures to implement these goals, then Executive Orders have the potential to have far-reaching results. As referenced above, the true impact of any particular law or policy will depend in large part on the level of enforcement and implementation in practice.

J40: Red States

Some states with Republican supermajorities are also starting to take steps to implement Justice40, including creating Justice40 oversight committees. In Missouri, the Senate passed a concurrent resolution suggesting that the Governor create a Justice40 oversight committee; however, the Governor has yet to establish such a committee. In South Carolina, a bill to create a Justice40 oversight committee is still pending in the legislature.

Alternative Legal Avenues for Implementing Principles Found in the Example Policies Above

If passing legislation on these issues is not a viable option in a particular state, there are other legal avenues for developing definitions for DACs, embracing community engagement principles, and implementing Justice40. The power to implement these policies are also available to other governmental bodies, such as state agencies and local governments.

State agencies, such as the State Energy Office (SEO), the State Department of Transportation, the applicable utilities or public services commission, are capable of promulgating and implementing powerful regulations and issuing program guidance to ensure the equitable distribution of federal funding within that state agency’s particular jurisdiction. State agencies have varying levels of jurisdiction over a wide range of issues, such as protection of the environment, transportation, and infrastructure. Depending on an agencies’ jurisdictional purview, policies relating to defining DACs within the context of state agency programs, implementing community engagement principles, and implementing the Justice40 Initiative, may fall within an agencies’ regulatory authority.

One example of a strong community engagement program is the Hawai’i SEO’s Clean Energy Wayfinders program, in which the Hawai’i SEO hires community members to serve one-year terms as liaisons between communities and the SEO, as community educators, and as resources for implementing energy efficiency practices, with an emphasis on targeting low- to moderate-income, asset-limited, income-constrained, employed, and under-resourced communities.

Similarly, local governments, when applying for funding from the state or federal government, can take action to advance Justice40. Local governments that apply for federal funding can include in grant applications a request to use the funding to hire a community representative to serve as a community liaison. Several federal programs support such hires to expand workforce development and equity. One such example comes from the City of Sommerville, which is currently seeking a Community Engagement Specialist to help incorporate community feedback in funding decisions. Building policies and human infrastructure to support equity in local government’s programs can help ensure that decision-makers are embracing community engagement principles in clean energy, infrastructure, water, and a number of other areas that impact public health and equity.

In the absence of clear law and policy, state and local decision-makers can look to helpful community engagement and Justice40 Implementation Guides developed by frontline communities and nonprofits that provide tangible suggestions for how to ensure meaningful community engagement in decision-making and the allocation of resources. Decision-makers can use these tools to identify and collaborate directly with communities to identify community needs and incorporate them into grant proposals. These benefits can be enforced through partnership and funding agreements between local governments and communities, including community benefit agreements, to help ensure benefits are realized in DACs consistent with Justice40.

Patterns Found in Our Research

In our research, we have identified several patterns regarding the state-level approach to identifying disadvantaged or vulnerable communities. Most states have a DAC definition in either the clean or drinking water context (most likely due to the SDWA amendments of 1996), but only 16 states, including Washington D.C., have an established definition in the climate or equity space; however, 25 states have DAC definitions when you add in the SRF affordability criteria in the clean and drinking water context.

This map focuses solely on definitions in climate, energy, and equity.

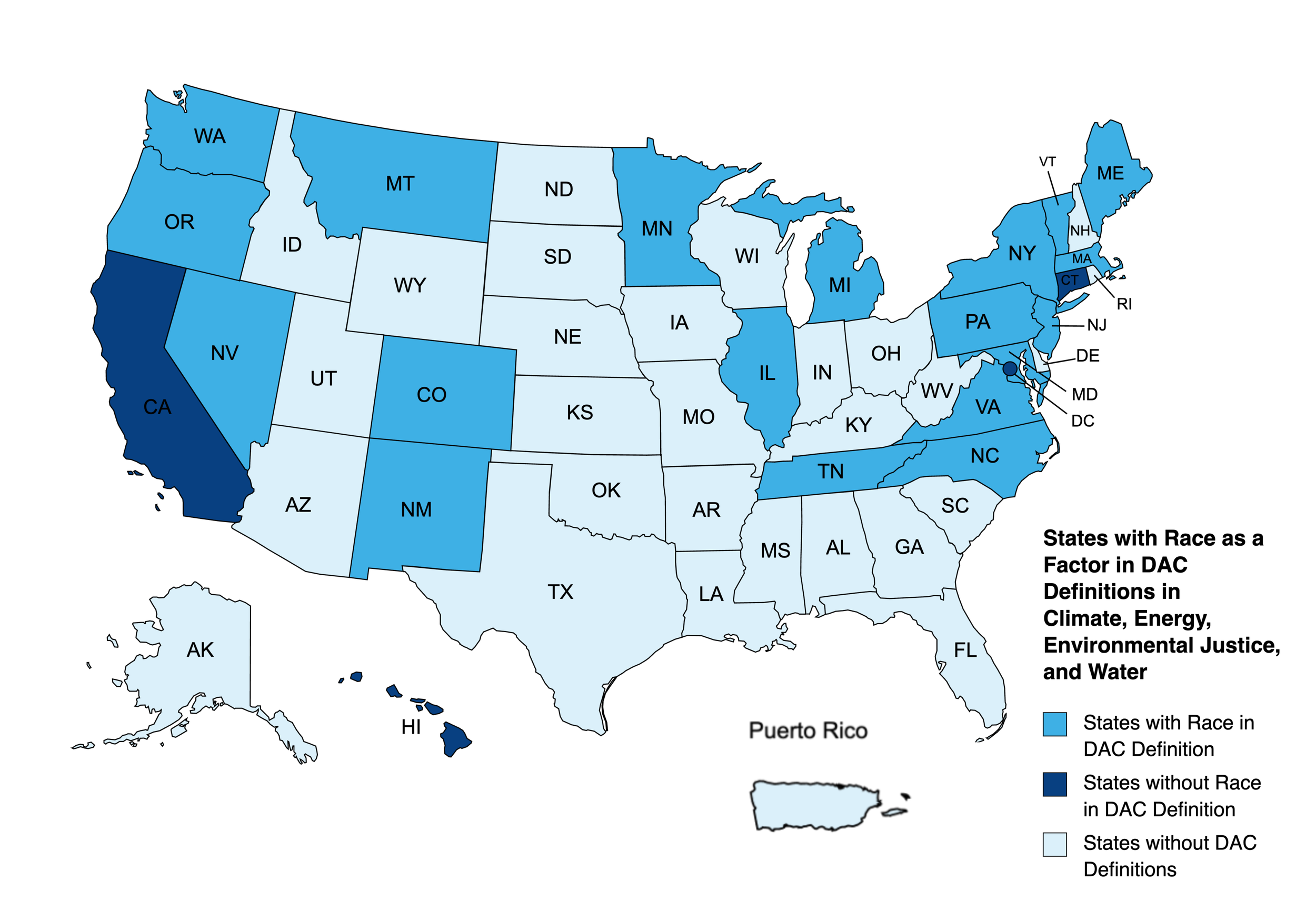

For the 25 states with DAC definitions (collective total of states with DAC definitions in either climate, equity, or the SRF affordability criteria context), 21 of the states use race in their definitions, while four states have DAC definitions that do not rely on race.

This map focuses solely on states with race as a factor in their DAC definitions in climate, energy, environmental justice, and water criteria.

On June 29, 2023, the U.S. Supreme Court issued a decision in Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard, a case concerning the use of affirmative action policies and procedures in two universities, Harvard College and the University of North Carolina. The Court held that the use of affirmative action policies at these two universities violates the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. Despite the monumental consequences of this case for the college admissions process and diversity, equity, and inclusion in the United States as a whole, the holding is quite narrow in scope in that it only applies to college admissions processes. However, this holding could be the beginning of the application of the principles backing the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision more broadly, as it could foreseeably begin to expand into other targeted areas of the law. Even though the affirmative action cases have a limited holding, it’s possible that some state actors will use the ruling as a basis for challenging state-level definitions that include race as a factor.

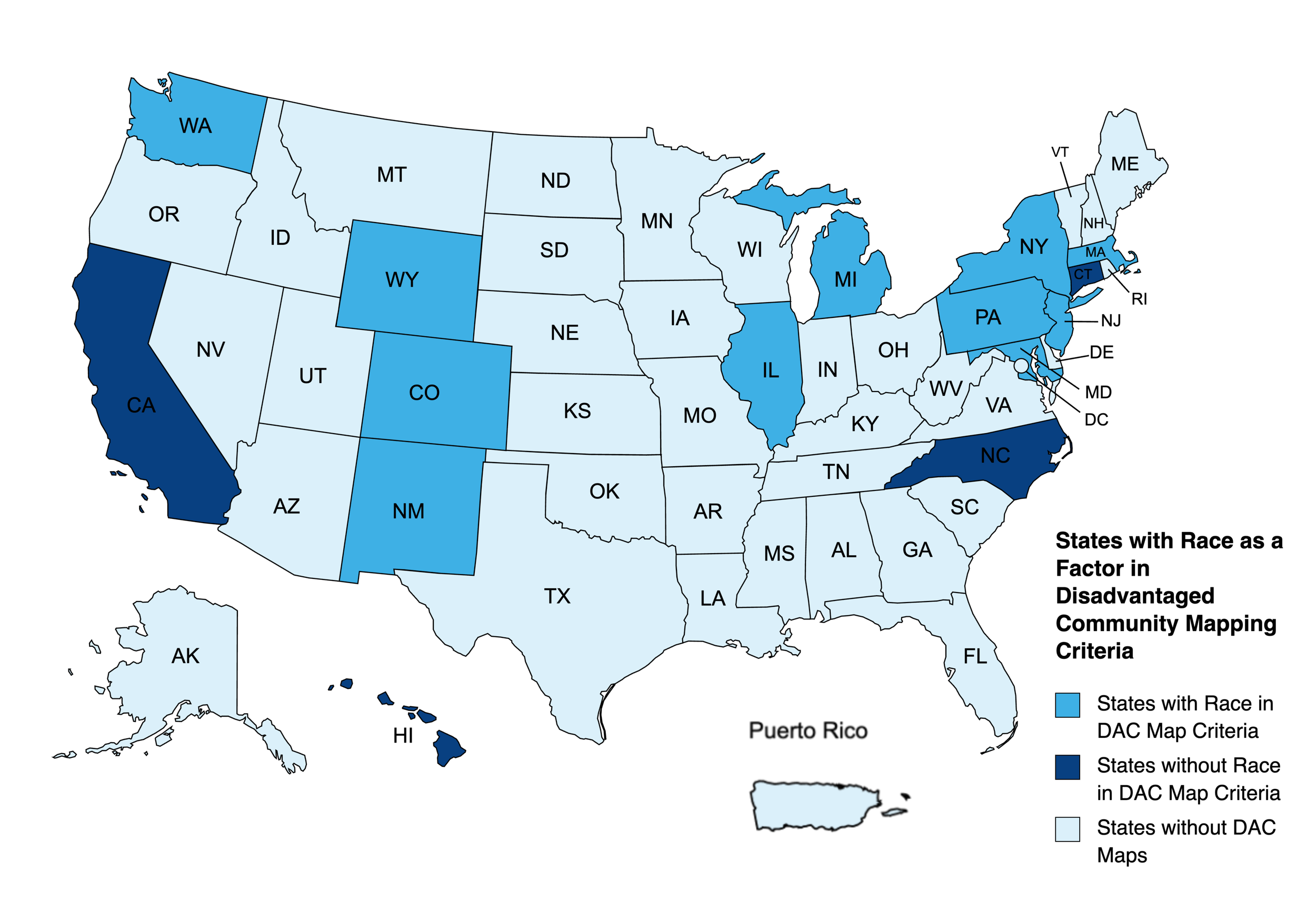

In contrast to states with formal DAC definitions in energy and climate, there are states that have a separate DAC mapping tool. For states with an existing DAC mapping tool, 11 states consider race as a criteria in designating underserved communities, and four do not include race in their criteria at all.

This map focuses solely on states with race as a factor in their DAC maps.

With respect to state-decision makers, we note that while the White House asked all states to identify a specific infrastructure manager or coordinator for BIL and Justice40 implementation, only 25 states have publicly identified such a manager, while some states (including Delaware) appear to have infrastructure managers identified internally. For states without a public-facing infrastructure manager, it will be more difficult for community leaders to meaningfully engage on infrastructure and funding decisions, which runs counter to the goals of Justice40. For these states, the State-Level Findings identify the relevant head of the State Department of Transportation who is often tasked with making federal funding allocations related to infrastructure.

Limitations and Caveats

The area of equity and climate funding law is rapidly evolving. This report provides data researched as of August 2023, but we anticipate that new and proposed regulations will continue to be released by states as more federal funding programs are announced and as the CEJST Map is revised. This report will be updated as new information becomes available.

If you have a proposed update to the findings in your state, please click here.

State-Level Findings

To view state-level findings, please click on one of the state names listed below. If you have a proposed update to the findings in your state, please click here.

This work is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0.

Footnotes

Under the CWA, affordability criteria should be based on income and unemployment data, population trends, and other data determined relevant by the State. 33 U.S.C.A. § 1383(i)(2)(A)(ii)

The following section identifies example policies that appear, on its face, to have helpful language regarding community engagement principles and equity, DAC definitions and implementing Justice40. L4GG has not completed an in-depth study of each of these example laws and policies to weigh on each law or policy’s efficacy in practice.

“Blue” states are states with Democratic majorities in both legislative chambers and the office of the governor. “Red” states are states with Republican majorities in both legislative chambers and the office of the governor. “Purple” states are states with bipartisan leadership.

The criteria can be found in the Technical Documentation related to the Draft Disadvantaged Communities Criteria.

Note that this total includes any state that has established a system for prioritizing resources to disadvantaged communities, but does not include states that only reference Justice40 tangentially in NEVI Plans.

For the purposes of this section of the report, the term “states” includes Washington D.C. and Puerto Rico.