NO TIME TO VOTE

Addressing Racial Inequity in Paid Time Off on Election Day

Summary of Findings

Historically, the United States has denied the right to vote and instituted monumental barriers to vote for Black people, women, Native Americans, non English speakers, persons with disabilities, low-income individuals, people with felony convictions, and others.

Many legal barriers remain today, including strict voter ID, “exact match” voter registration, voter purges, and cuts to polling locations, that particularly target Black and Brown communities, and make it harder for them to vote.

After the Shelby Supreme Court case in 2013, states with histories of racism that previously needed federal approval to change their voting laws started enacting new laws and practices. Federal courts have found that many of those laws systematically discriminate against Black and Brown voters.

During the 2016, 2018, and 2020 elections, Black and Brown voters waited longer to vote than white voters. In 2016, voters in all-Black communities waited 29% longer than voters in all-white communities.

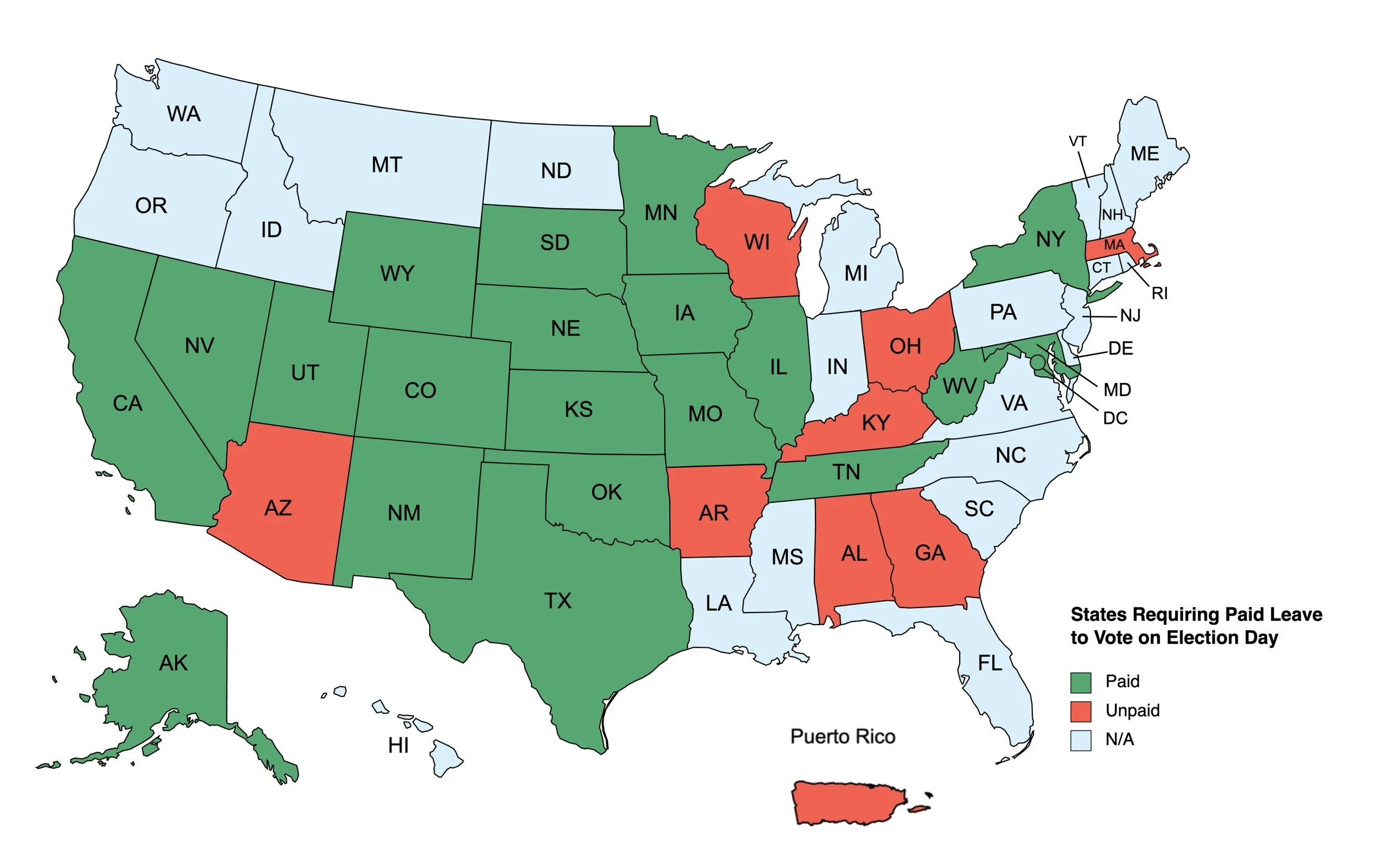

28 states, D.C., and Puerto Rico require employers to allow their employees time off to vote on Election Day.

Of these, only 20 states and D.C. require paid leave.

8 states and Puerto Rico require leave that is unpaid.

Most states that require leave to vote cap the time requirement at one, two, or three hours, even though voters must often stand in line for far longer, forcing them to choose between their income and exercising their right to vote.

Four states (Hawaii, Oregon, Vermont, and Washington) have authorized all-mail-in voting for all elections, which allow many workers to vote without needing to leave work.

There is growing momentum toward requiring employees to be able to leave work to vote on Election Day.

The District of Columbia (2020) is the latest jurisdiction to require paid leave for voters.

Legislators of both parties have introduced bills in recent years to require their states to establish time off to vote in at least nine additional states.

-

The right to cast a ballot is viewed by many as one of the most basic and fundamental rights of living in a free democracy. The act of voting is not merely a personal choice to make one’s voice heard during an election, but is essential to guaranteeing our self-governance and individual liberty, and providing an essential check on governments who encroach upon that liberty. The U.S. Congress and Supreme Court have called the right to vote a fundamental right. However, fundamental rights must be protected. The discriminatory history of exclusionary voting laws in this country show that lawmakers and the courts have not given voting rights the same deference and scrutiny as other fundamental rights.

Strict prohibitions of and oppressive barriers to the franchise have long been a moral stain on the history of American democracy. The Constitution contains no explicit right to vote, and the Fifteenth Amendment protects the right to vote only from being “denied or abridged...on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” From the beginning, people have been denied equal representation, and forced to overcome tremendous barriers to vote, particularly Black Americans, women, Native Americans, non English speakers, persons with disabilities, low-income citizens, and other communities. The Fifteenth Amendment did not prevent states from enacting poll taxes, literacy tests, and obstacles to deny Black people the vote in the Jim Crow south. While the Nineteenth Amendment granted most white women the right to vote, it excluded Black, Brown, Indigenous and Asian immigrant women. The Indian Citizenship Act of 1924 granted citizenship, but forced Native Americans to fight state by state for the right to vote until 1962. The “English Only” movement continues to target non-English speakers and those more comfortable communicating in other languages by advocating that government documents, including ballots, only be printed in English. States have used the Americans with Disabilities Act as an excuse to close polling places in majority-Black and Native American counties, thereby pitting one civil rights law against another. And the U.S. continues to deny statehood for the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico, restricting the right to representation of millions of American citizens of color, and even refuses to grant the most basic right of citizenship to residents of color in American Samoa.

Long after the historic Voting Rights Act of 1965 [“VRA”] was passed to eliminate many types of racial discrimination in voting, there remain legal barriers that especially keep communities of color from voting, and dilute their power when they do. Millions of citizens convicted of felonies, who are disproportionately Black, remain ineligible to vote, even long after completing their sentences. Black Americans are already charged and sentenced at higher rates than whites for the same crimes. Afterward, Black Americans of voting age are disenfranchised at a rate of more than four times that of non-Black Americans. The Electoral College empowers white and rural voters over Black and Brown voters in urban areas. And in 2013, the Supreme Court’s decision in Shelby County v. Holder opened the floodgates for states to enact new, legal voter suppression laws targeting communities of color. By removing federal oversight of changes to election laws in states with histories of race discrimination, the Court stripped the Department of Justice of one of its primary authorities to curtail racism in state voting laws. As a result states quickly enacted new voter suppression laws that would previously have been denied under the VRA. Many of these laws have been struck down by federal courts as “motivated at least in part by an unconstitutional intent to target African American voters,” and drafted with “almost surgical precision” to suppress Black voters.

Before Shelby, these states needed DOJ clearance to change election laws by showing that there would not be a discriminatory impact on Black voters and communities of color. Since Shelby, states can now make changes without having to get permission from the DOJ. Since the 2020 election, at least nine states have passed voter suppression laws, and the past few years have seen hundreds of anti-voting bills introduced in at least 48 states.

Some of these new laws and practices, including voter ID, “exact match” voter registration, and voter purges, may seem to be racially neutral, but have been shown to suppress minority voters of their rights by making it more difficult to vote. For instance, under the guise of combating voter fraud, which studies show is extremely rare, states have enacted strict voter ID requirements, even though millions of Americans, disproportionately people of color, lack the required identification. After Georgia established an “exact match” voting law, approximately 80 percent of people whose registrations were blocked were people of color. And voter purge rates in jurisdictions previously covered under the VRA are 40 percent higher than in other jurisdictions.

“The discriminatory history of exclusionary voting laws in this country show that lawmakers and the courts have not given voting rights the same deference and scrutiny as other fundamental rights.”

-

Between 2012 and 2018, states formally under federal oversight under the VRA closed 1,688 polling places. Many of these jurisdictions are also experiencing increased voter registrations, particularly in communities of color, crowding more Black and Brown voters into fewer polling locations. Over this time, the average number of voters assigned to polling locations grew in South Carolina, Georgia, Mississippi, and Louisiana, states that the VRA previously required to get DOJ clearance.

In Texas, state officials targeted Black and Latino voters by deciding that almost three-fourths of poll location closures would be in counties that saw the highest increase in Black and Latino voters during this period.

Georgia’s decision to reduce the number of polling locations statewide caused long lines in majority-Black neighborhoods. Since Shelby, nearly two million new voters have registered, but Georgia closed 10% of polling locations. As a result, the number of voters assigned to each polling location has grown by almost 40%. During the 2020 election, voters in Georgia waited in hours-long lines, sometimes up to eleven hours.

During the 2016, 2018, and 2020 elections, Black, Brown, and low-income voters waited in longer lines to vote than people in whiter and more affluent communities, and race was the strongest determinant of longer wait times. Voters in all-Black communities waited 29% longer in line to vote compared to voters in all-white communities, and were 74% more likely to spend over 30 minutes to vote.

These are policy decisions, nominally about the allocation of resources, but more aptly about deciding which part of the electorate should have an easier or more difficult experience voting, and ultimately, whose voices should be prioritized in electoral outcomes. Long lines suppress current voters and future turnout as well.

-

Although the voting landscape continues to change, which may enable more people to vote early or absentee, significant numbers of people continue to vote in person on Election Day. While as a nation we have progressed beyond the overt racism of poll taxes and literacy tests, a persistent barrier has been long lines to vote and the so-called “time tax,” which taxes Black Americans more heavily.

The United States is currently one of only nine member countries of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development to hold elections on a weekday. Federal and state laws should not require voters to risk their income by exercising their right to vote. For workers paid by the hour, lost time means fewer earnings. Even among states that do allow for paid time off, the amount of time may be insufficient for those who lack transportation, who must travel longer distances and stand in longer lines in counties with fewer polling locations, and those whose job or family care obligations may prevent them from voting altogether.

Although many structural changes must occur, one small step is for states to require that employees have time to vote without penalty or loss of wages. Close to 60 years after the ratification of the 24th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution outlawed poll taxes, workers should not have to pay to vote, nor should they be forced to decide between exercising a fundamental right over their income.

Companies increasingly agree with this principle. Currently, almost 2,000 corporations have become members of Time to Vote, empowering their employees to take paid leave to vote. Additionally, over the past four years, legislators of both parties in nine states without required leave have introduced bills to require leave in their state, although most would still fail to guarantee an adequate amount of paid leave time. This represents a growing shift in culture and the law, and it is time to ensure that all employees have this right, regardless of their state or employer.

States Requiring Employee Leave to Vote on Election Day

-

Federal law does not require employers to provide leave for employees to vote, and state laws vary with regard to requiring leave, how much leave can be taken, and whether leave is paid or unpaid. 28 states, D.C., and Puerto Rico require employee leave time to vote on Election Day. while 18 states do not. 4 states (Hawaii, Oregon, Utah, and Washington) have established all-mail-in voting for elections.

Only 4 states guarantee employees the full amount of time necessary to vote. One state requires four hours of leave, 5 states require three hours of leave, fifteen require two hours of leave, two require one hour of leave, and four provide an unspecified or “reasonable” amount of leave.

However, this is too often insufficient, when states from Alabama to Wisconsin, and Arizona to Ohio force their residents to wait several more hours in line to vote, and make the difficult choice of whether to stay and cast a ballot while jeopardizing their income.

Of the states that require leave on Election Day, 20 states and D.C. require paid leave for all workers while 8 states and Puerto Rico require unpaid leave.

*Hawaii, Oregon, Vermont, and Washington have established all-mail voting for all elections

States Requiring Paid Leave to Vote on Election Day

State-Level Findings

To view state-level findings, please click on one of the state names listed below. If you have a proposed update to the findings in your state, please click here.

If you are a legislator and would like to receive assistance related to this project, please fill out this form.

If you work for a non-profit and would like to partner to create a similar report on an issue that has a disproportionate effect on one or more marginalized communities, please fill out this form.